Getting Leave to the Supreme Court of Canada: 2025 by the Numbers

As part of Lenczner Slaght’s Data-Driven Decisions program, our readers know we maintain a comprehensive database capturing every Supreme Court of Canada leave decision since January 1, 2018.

We use that data in two ways:

- To power our machine‑learning model that predicts the likelihood of leave to appeal.

- To track how the Court is evolving over time.

This post does exactly that. Using our dataset, we take a data‑driven look at what happened at the Supreme Court of Canada in 2025, and what those patterns may signal for litigants considering a trip to Ottawa.

Leave Grants: Lower Than Average, But Not Rock Bottom

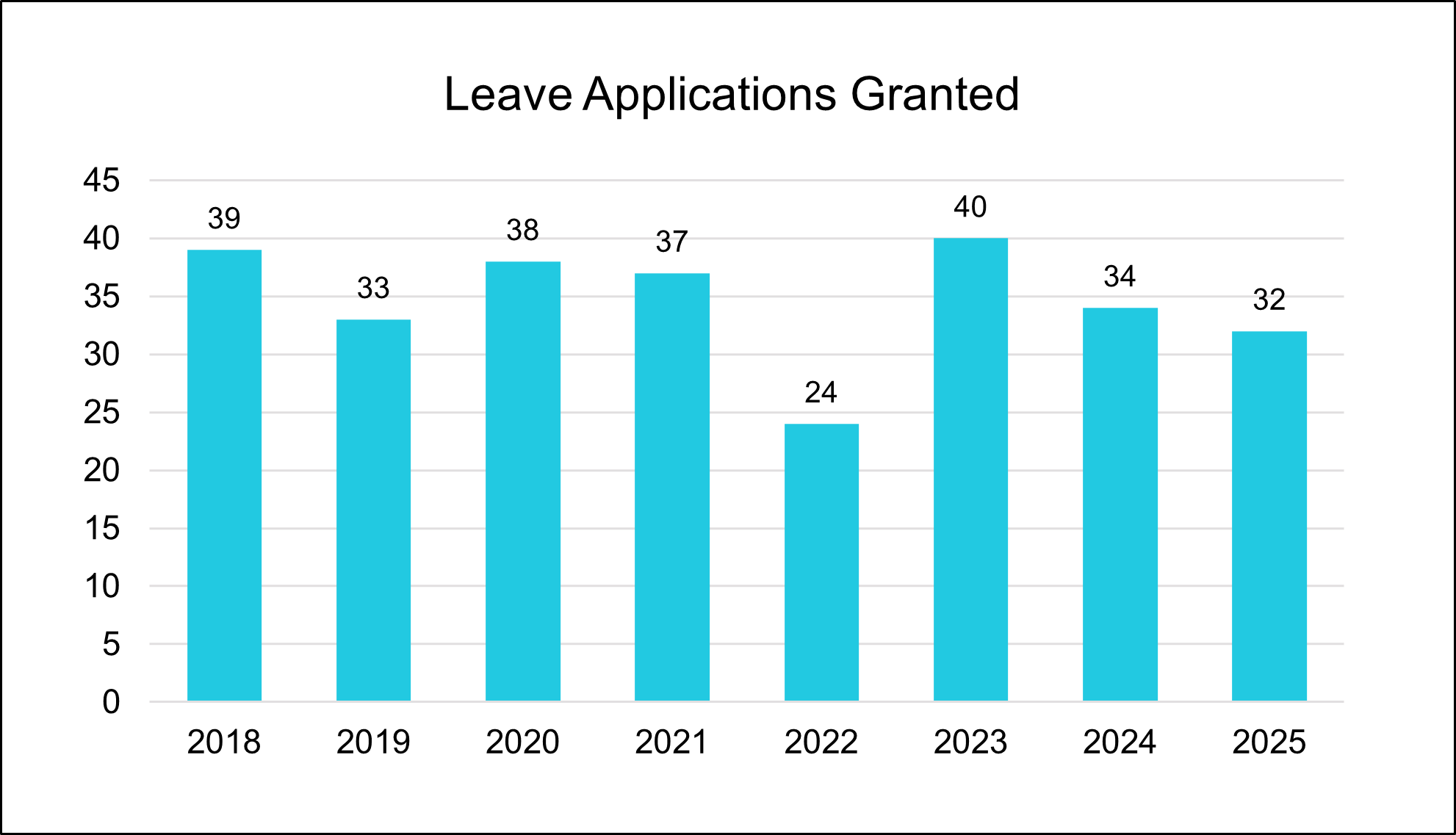

The headline number for 2025 is straightforward: the Court granted leave in 32 cases.

That figure is below longer‑term historical averages and down from recent years (40 grants in 2023 and 34 in 2024) but is well above 2022’s low of 24. In other words, 2025 was a quieter year – but not an anomalously restrictive one.

Fewer Decisions, Not a Tougher Court

The modest decline in leave grants in 2025 was not driven by a change in the Court’s appetite for cases. Instead, it was the mechanical result of fewer leave applications being decided at all.

As the data show, the total number of leave applications decided dropped meaningfully in 2025, especially in cases where applicants were represented by counsel.

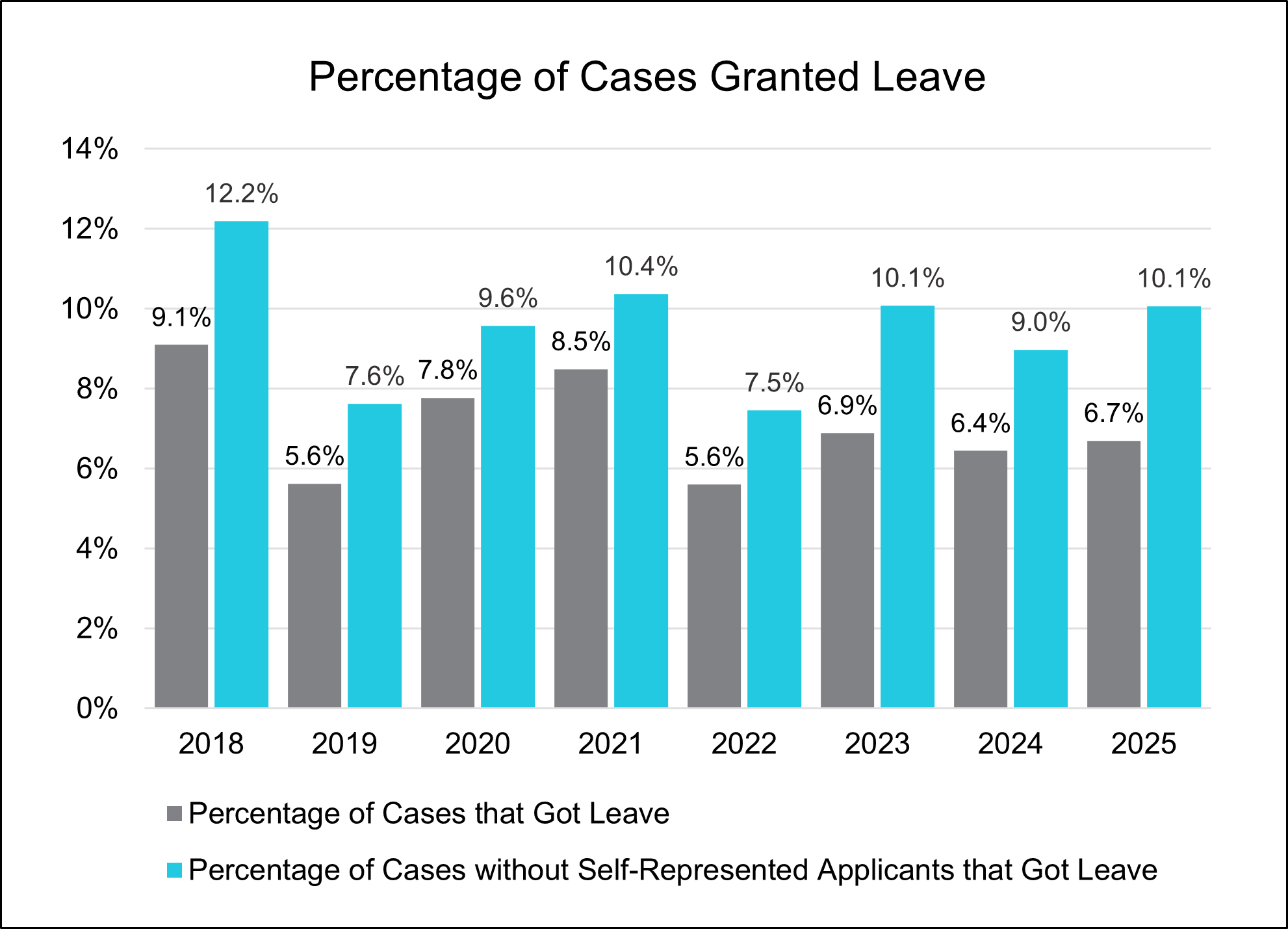

This distinction matters. Unrepresented leave applications are almost never granted. The realistic pool of potential grants is overwhelmingly limited to cases with counsel on record. In 2025, that pool shrank: only 318 represented leave applications were decided, the lowest figure in any year in our dataset.

By contrast, grant rates themselves were strikingly stable. Overall, 6.7% of leave applications were granted in 2025. Among represented applicants, the grant rate was 10.1%, almost identical to prior years. The Court was not tougher; it simply had fewer serious contenders before it.

Public Law Takes Centre Stage

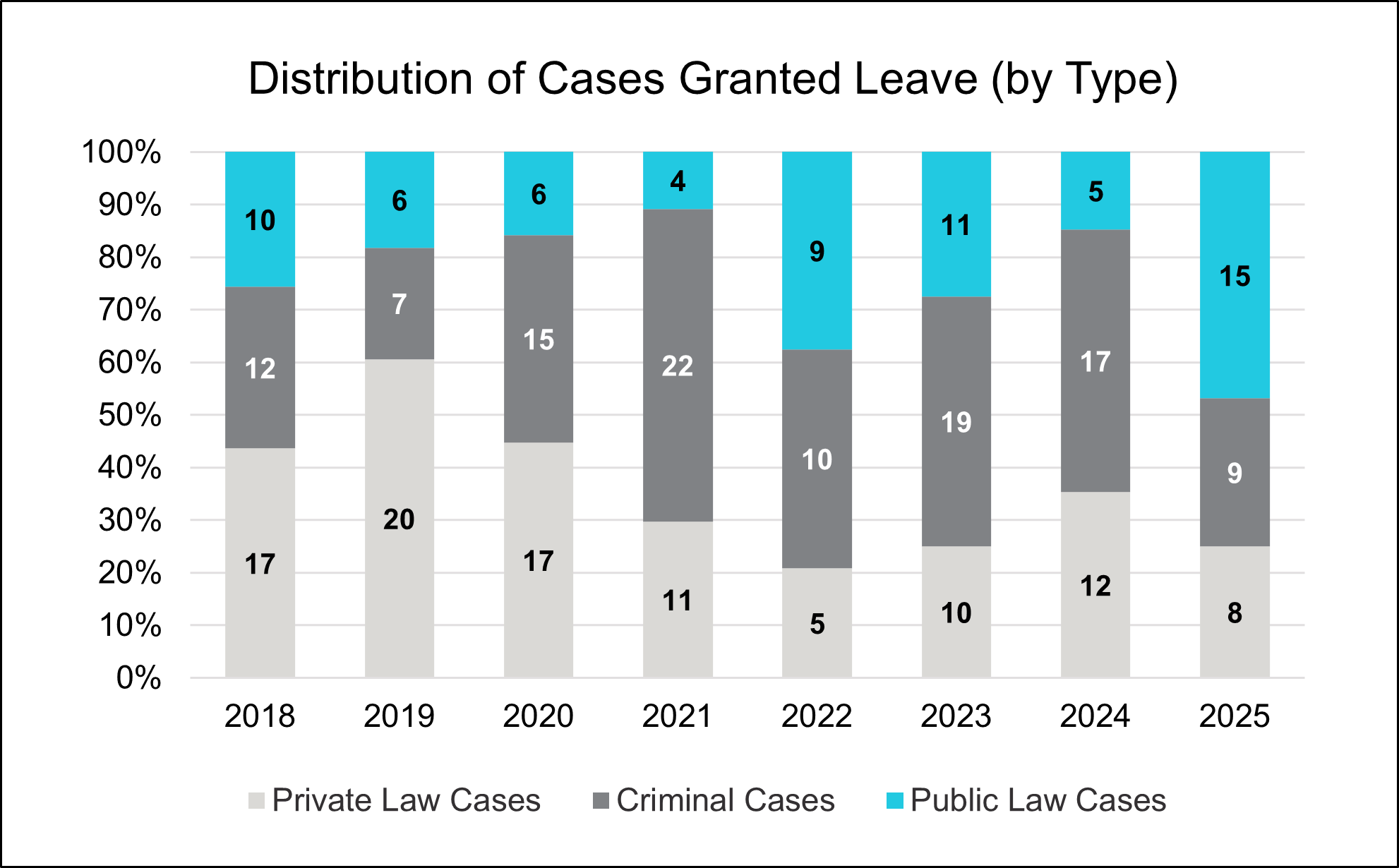

We track subject matter at a granular level, but for present purposes it is helpful to group cases into three broad categories: private law, criminal law, and public law.

Looking first at leave applications decided, private law continues to dominate the docket. In 2025, private law cases accounted for 46% of all leave applications decided, with criminal and public law cases roughly splitting the remainder.

The picture changes dramatically once we look at leave grants.

For civil litigators hoping that 2024 marked the start of a private‑law resurgence, 2025 was a disappointment. Only 25% of cases granted leave were private law matters. Criminal cases did not fill the gap. Instead, public law emerged as the clear winner: nearly half of all leave grants in 2025 were non‑criminal public law cases.

The signal is a familiar one. Where issues of governance, administrative power, and constitutional structure are in play, the Court continues to show a strong appetite for intervention.

A Broad but Predictable Geographic Mix

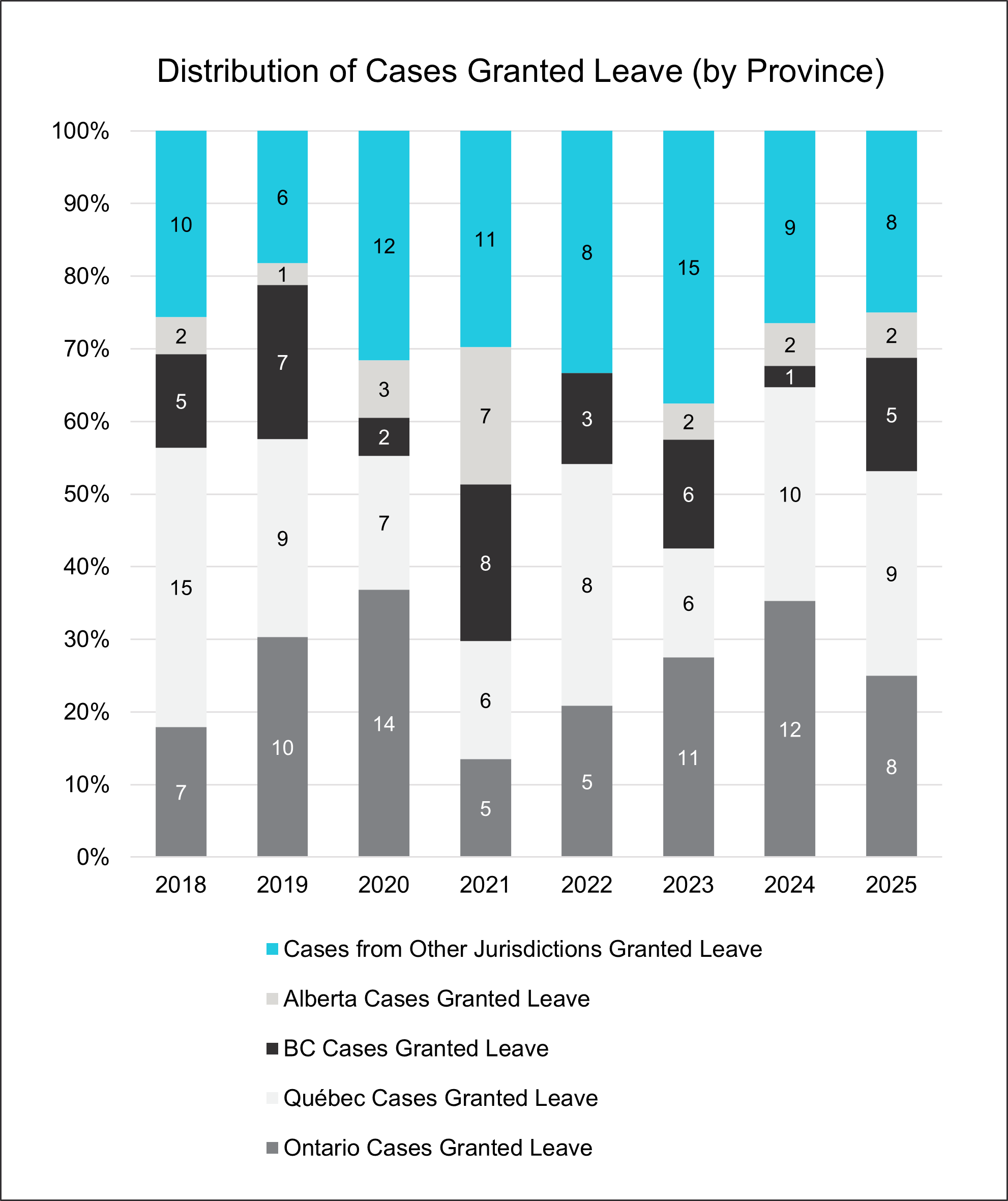

Geographically, 2025 looked much like prior years. Ontario and Québec together accounted for just over half of all leave grants, consistent with their share of appellate litigation nationally.

At the same time, the Court continued to draw cases from across the country. Leave was granted to cases originating in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Federal Court of Appeal, reinforcing the Court’s role as a genuinely national institution.

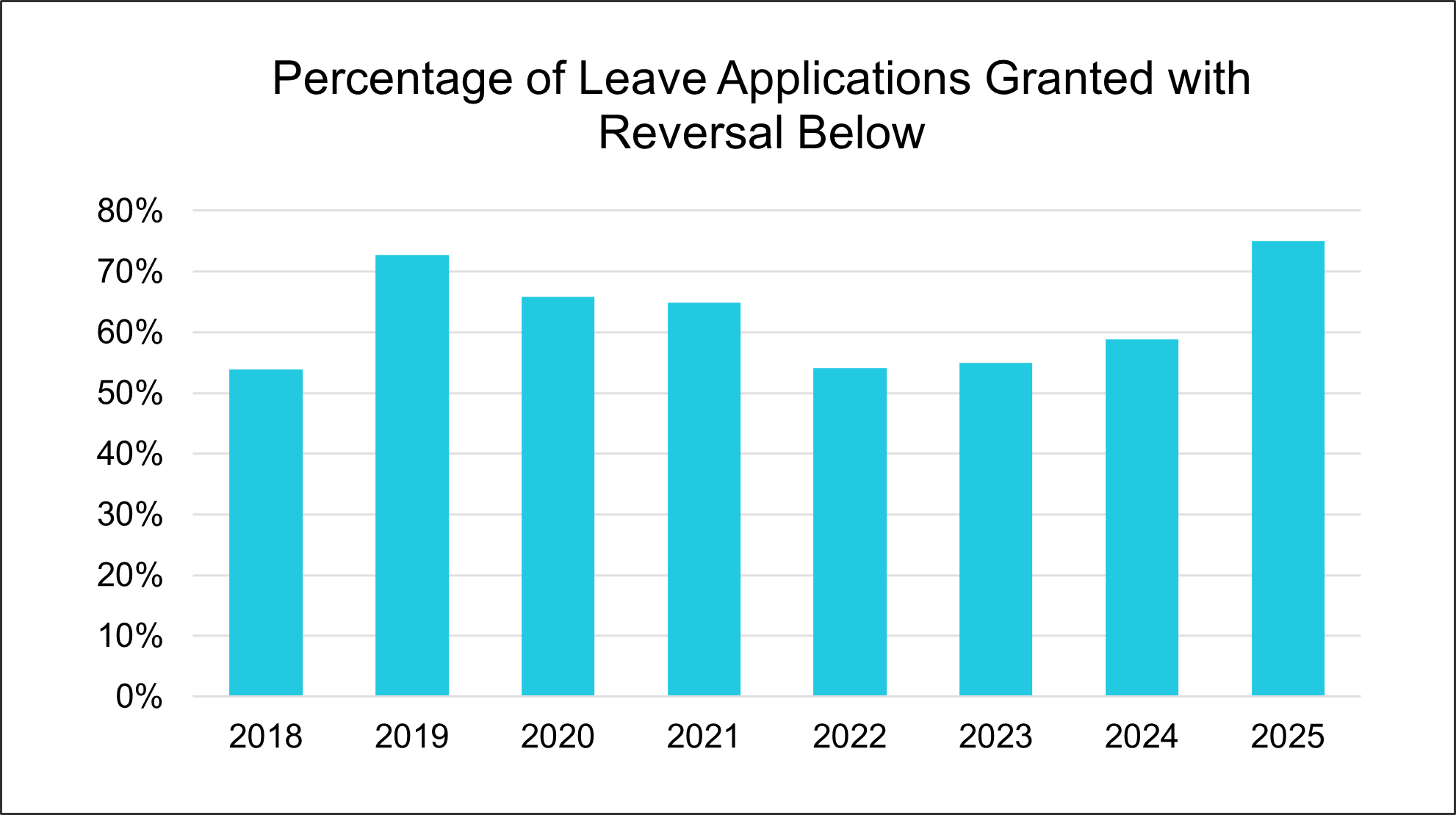

Conflict Below Remains a Powerful Signal

Our analysis has long shown that many of the strongest predictors of leave are tied to one core idea: controversy in the courts below.

One simple proxy for that controversy is whether the intermediate appellate court overturned the decision at first instance. Year after year, more than half of successful leave applications involve exactly that fact pattern.

In 2025, the relationship was even stronger: 75% of cases granted leave involved an appellate reversal of the trial decision. Disagreement, either explicit or implicit, continues to be one of the clearest signals an issue may be ripe for Supreme Court review.

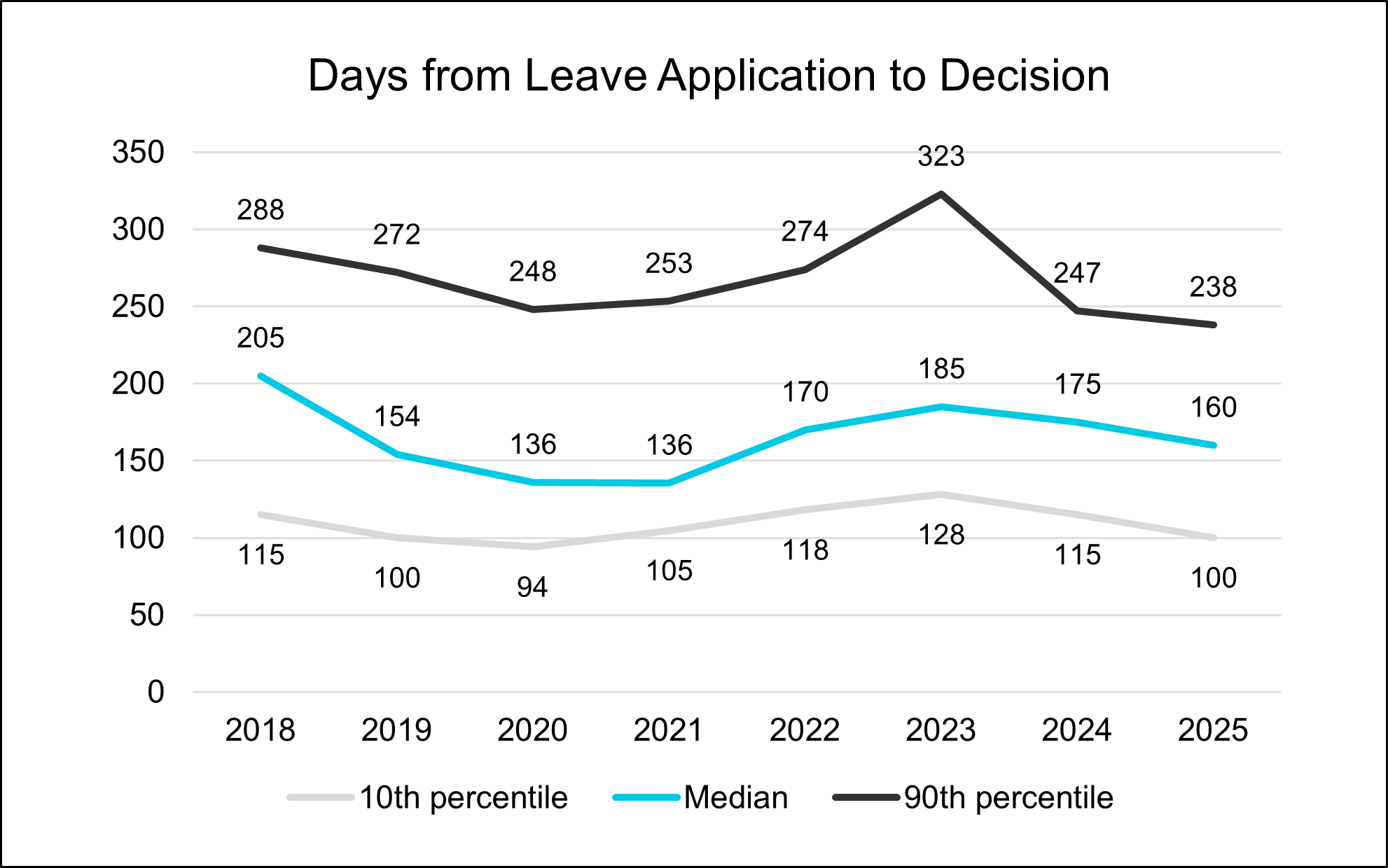

The Timeline from Leave Application to Decision

There was good news in 2025 on timing of getting leave applications decided.

From 2018 through 2020, the Court steadily reduced decision times for leave applications, with the median dropping from 205 days to 136 days. After a pause in 2021, timelines lengthened again, reaching a median of 185 days in 2023. That trend began to reverse in 2024 and continued in 2025.

In 2025, the median time to decide a leave application was just 160 days.

More notably, the longest‑running cases moved faster as well. The 90th percentile fell to 238 days, meaning 90% of leave applications were decided within eight months of filing. This is the lowest 90th‑percentile figure in our dataset, suggesting meaningful progress in managing the Court’s most time‑consuming cases.

Conclusion

Taken together, the 2025 data paint a coherent picture. The Supreme Court of Canada did not materially change its standards for granting leave. Instead, the year was shaped by volume effects, a continued emphasis on public law, and a persistent focus on cases that reveal disagreement or instability in the law.

For litigants and counsel, the lessons are familiar but worth repeating: strong cases for leave tend to involve real doctrinal tension, clear appellate disagreement, and issues that resonate beyond the parties themselves. Our data, and our models, continue to reflect that reality.